Source: Combined Authorities (England)

Author: Rob Hakimian

Date published: 2025-09-16

[original article can be accessed via hyperlink at the end]

The previous government cancelled HS2 North and slashed Northern Powerhouse Rail, but the need for improved rail connections in the North of England can’t be ignored, so local authorities are piecing together the plans themselves.

In October 2023, when former prime minister Rishi Sunak announced the cancellation of High Speed 2 (HS2) between Birmingham and Manchester, he was finishing off the work started by the Boris Johnson government with the Integrated Rail Plan for the North and Midlands (IRP).

Published by the Department for Transport (DfT) in November 2021, the IRP did not, as suggested, set a grand vision for the future of rail connectivity in the North and Midlands, but in fact scaled back on long-promised plans.

The HS2 Phase 2b eastern leg from Birmingham to Yorkshire was scrapped entirely while the all-new railway running east-west to connect the cities of the north, known as Northern Powerhouse Rail (NPR), was scaled back to its “core network”. NPR had been promised since 2015 as a signature “levelling up” project for the North, but the IRP scaled it back to 64km of new track from Liverpool to the very western edge of West Yorkshire, along with some upgrades that would not rectify the connection and capacity problems in cities like Leeds and Bradford.

In the two years after the IRP, hardly any of the promised work had progressed and turmoil around HS2 Phase 1 – between London and Birmingham – had continually swirled in the media. That was the background when Sunak lopped off the last remaining arm of the country’s great infrastructure project at his party’s conference.

“I suspect he made the decision to try to win votes, but he judged it completely wrong,” says West Midlands Combined Authority head of HS2 and strategic partnerships Craig Wakeman. “What he did was leave the country in a position where the opportunity to stimulate growth between the Midlands and the North is impacted and somewhat inhibited.”

However, the affected regions were not content to sit idly by. The mayors of Greater Manchester and the West Midlands, Andy Burnham and then Andy Street, drew up a new plan with the help of private entities.

“I was called into Andy Street’s office the day after HS2 North was cancelled and five days later the consortium led by Arup was already mobilised,” Wakeman says.

Burnham was also working with Liverpool City Region mayor Steve Rotherham to convene a group to develop a new Liverpool-Manchester Railway (LMR), intended as the first step towards NPR. Similarly, this group brought together both public and private sector expertise and Arup took the lead in drawing up a new plan.

The government changed in summer 2024 and the new Labour leadership announced grand plans for reforming the country’s railways. While it dismissed the idea of reviving HS2 North, it seemed willing to hear alternative proposals.

The proposal for a Midlands-North West Rail Link (MNWRL) to connect Birmingham and Manchester was published by the consortium on behalf of the two combined authorities in September 2024. This was followed by the prospectus for LMR, put together by Arup on behalf of 12 local authorities, in May 2025.

Unlike plans for HS2, these strategies talk little about improved journey times, with the proposals’ focus on stimulating economic growth in the regions.

“The government doesn’t want to buy a railway necessarily, it wants to buy economic growth corridors,” Wakeman says. “That’s what we’ve got to work towards for the future; we have to do something to allow us as a country to increase our productivity, increase our exports and to increase our living standards. We have to do something to address those economic growth corridors.”

Midlands-North West

The MNWRL plan was drawn up by Arup alongside Addleshaw Goddard, Arcadis, EY, Mace, Skanska and Dragados.

It put forward three concepts: improving existing infrastructure, a combination of upgrades and sections of new track or an entirely new line roughly 80km long. However, the plan concludes that the entirely new line is “the best path forward” as it is the one that makes most sense financially and can deliver the required capacity and economic uplift.

The proposed MNWRL line is not radically different to HS2. It follows the same corridor and one of the major benefits of adopting it is that it would “save the taxpayer £2bn on costs from the HS2 Phase 2 cancellation by re-using much of the land, powers and design work already secured through public investment”, according to the plan.

The difference between this plan and HS2 is the specifications: the trains would run at 300kph, down from HS2’s proposed 360kph; the route would be built to British rather than European specifications; it would be built on ballasted track instead of slab track; and it would have simplified interfaces with existing Network Rail infrastructure. With these changes, it is believed it would cost only 60-75% of the cancelled stretch of HS2.

Furthermore, it would be largely funded by the private sector.

“We believe that there is a model here for a private sector-led delivery,” says Arup chief officer for global business and markets Richard De Cani. “If you put the incentives in the right place and deal with the risk transfer in the right way, you can actually get a proposition from the private sector that’s lower cost and can be delivered quicker.”

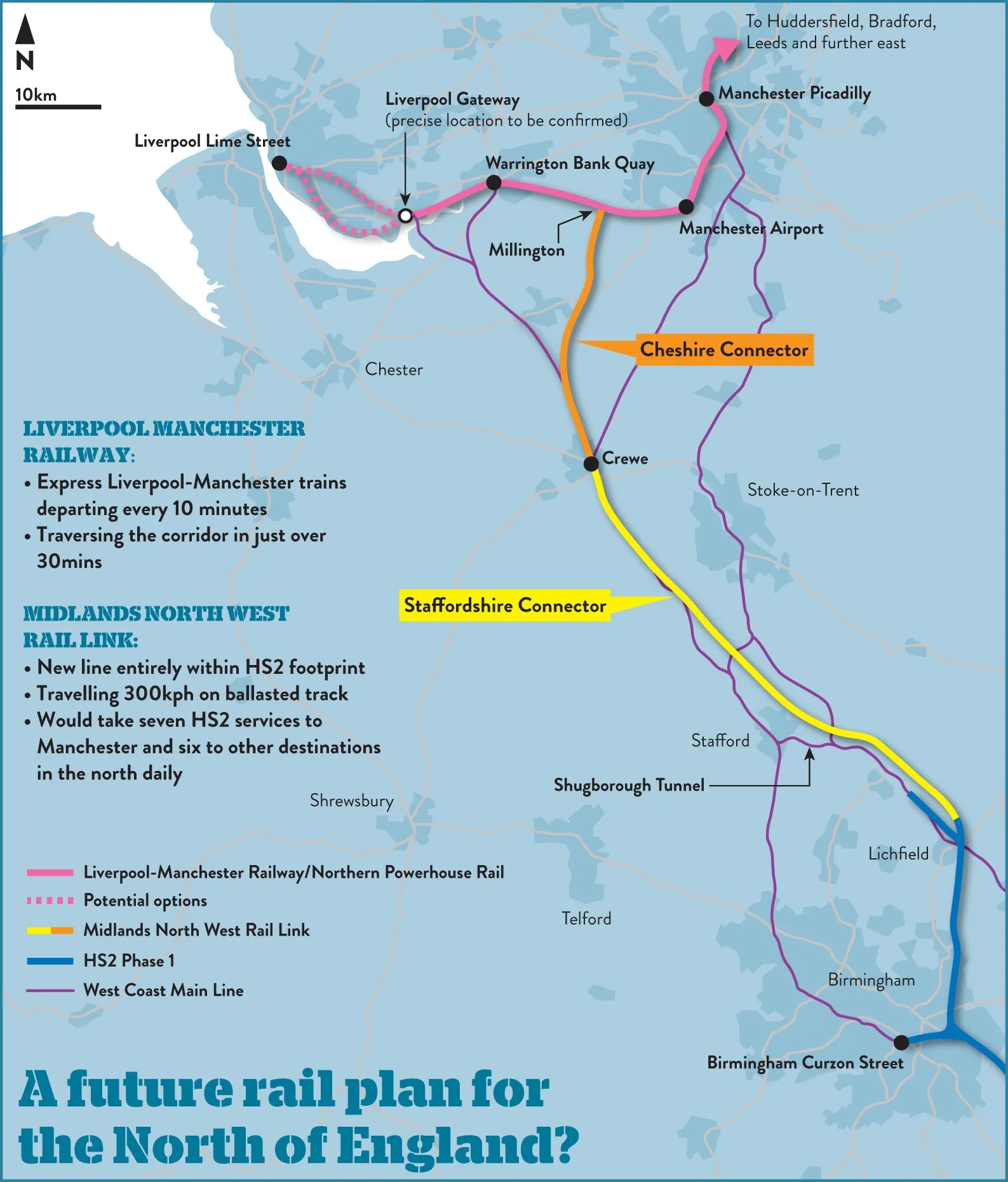

The MNWRL also mirrors the HS2 Birmingham to Manchester line in that it is split in the same place. What was formerly HS2 Phase 2a (Birmingham to Crewe) is now called the Staffordshire Connector and what was Phase 2b (Crewe to Manchester) is now called the Cheshire Connector.

This is crucial because Phase 2a still has planning approval, safeguarding and land purchase powers in place. This can be used for the Staffordshire Connector and should make it more attractive to private investment.

“Planning consent is a huge milestone for any infrastructure project,” De Cani says. “The private sector will think about risk and that’s number one on the risk register ticked off.”

The transport secretary recently gave an order to start selling off the land previously purchased for the HS2 leg to Leeds but has not made a call on the land between Birmingham and Manchester, suggesting there are still intentions for it

Another critical aspect of the Staffordshire Connector is that it will prevent what is shaping up to be a capacity crisis on the West Coast Main Line (WCML). A key part of the remaining HS2 is that trains will continue running up to Scotland on the WCML, but, without Phase 2a, HS2 trains will have to join WCML before Shugborough Tunnel. This is a known bottleneck where the tracks reduce from four to two and it is already at capacity.

“If you run an HS2 train on this route, you have to take out a classic train, which would leave stations south of Handsacre and potentially as far as Rugby with a reduced service,” explains independent rail consultant William Barter.

However, if the Staffordshire Connector is constructed, it enables HS2 trains to connect to the WCML north of Crewe, bypassing this bottleneck. “It’s so obvious it must be built for capacity and for economic reasons,” Barter says.

The clock is ticking, though. The compulsory purchase powers on this section expire in February 2026 – though the transport secretary can extend them. While there has been no word from the government as to whether it will make this decision, parties involved in the MNWRL are hopeful. Transport secretary Heidi Alexander recently gave the order to start selling off the land and property previously bought for the HS2 leg to Leeds but has not made any such call on the land between Birmingham and Manchester, suggesting the government still has intentions for it.

“It will never be easier to build that bit of railway [from Birmingham to Crewe],” De Cani says. “The land would be sold back at a loss, probably, because the government paid a premium for it, so that would be poor value for money.

“If you let the planning permission lapse, you will never come back to it again. This is a once in a lifetime opportunity to build a section of new railway between Lichfield and Crewe, parallel to the WCML, that would take away the capacity constraint on that section.”

The second half of the line, the Cheshire Connector between Crewe and Manchester, does not yet have planning permission – but it isn’t far off. The HS2 Phase 2b Bill was in its committee stage at the point when Sunak decided to cancel it, but the new government has already signalled its intention to revive and repurpose the Bill for NPR/LMR as it covers much of the same land needed between Manchester and Liverpool for that scheme.

This confluence of plans has already been mapped out by those involved in both the LMR and the MNWRL. It is something that De Cani hopes will be given more time for investigation.

“Of course, government needs to consider this carefully, but what it could do is form a steering group between itself, the two mayors and the private sector organisations involved and go through a six-month proper, paid piece of work,” he says.

“We can properly look at the different delivery models, how it could be funded, test the market, see how it’s happened elsewhere, look at the opportunities for simplifying design – all those things.

“If we get to the end of the six-month window and decide it’s not viable, at least we’ve had a proper look at it. So that’s our ask to government.”

Liverpool to Manchester

The mood music around LMR and NPR is positive. Aside from the announcement that the Phase 2b Bill will be repurposed for NPR, the government has promised to reveal its “ambitions” for the project this autumn.

This comes on the back of work done by the Liverpool and Manchester mayors, who set up the LMR Partnership Board, which is chaired by former rail minister Huw Merriman and brings together local stakeholders and representatives of private firms in the engineering, construction, finance and transport spheres.

The Partnership Board’s prospectus for LMR positions it as the backbone of what it is calling the “Northern Arc”. It has calculated that, with LMR, the Northern Arc could provide up to £90bn output for the national economy by 2040.

The proposal is for a brand new line from Liverpool to Manchester with five stops: Liverpool Lime Street, Liverpool Gateway, Warrington Bank Quay, Manchester Airport and Manchester Piccadilly.

“You’ve got five station growth zones that allow this to be an economic railway as well as improvement to transport,” Merriman says. “It’s the catalyst to continue the growth journey that the North West has been on.”

Under the proposal, Liverpool Gateway would be a brand new station with connections to Liverpool John Lennon Airport, Warrington Bank Quay would connect the line to the WCML, Manchester Airport would be a new station, and a new four-platform underground station would be created at Manchester Piccadilly that would enable through passage for future NPR services.

The LMR Partnership Board’s proposal is for a brand new line from Liverpool to Manchester with five stops: Liverpool Lime Street, Liverpool Gateway, Warrington Bank Quay, Manchester Airport and Manchester Picadilly

“This is very much part of NPR; that broader east-west connectivity across the North is really important,” adds Transport for Greater Manchester head of NPR and high-speed development Liz Goldsby. “It’s important that we tailor the development of the scheme to maximise that growth opportunity, as opposed to purely looking at it as a railway.”

This has meant that the LMR scheme has been developed in a “bottom up” fashion by working with all the local authorities in the area, according to Goldsby.

“We look at the railway as an enabler for the growth opportunities and by integrating that thinking and having a partnership approach, we can do that more effectively,” she says. “We’re avoiding the scenario of just building a railway; we’re thinking about how it plugs in locally, in terms of both development and public transport, so that we’ve got an integrated solution.

“More local input means we can work with government properly to help deliver the programme, rather than just be a stakeholder.”

The LMR Board is continuing to engage with the DfT on the scheme but is awaiting its official announcement on exactly what it intends for NPR. Merriman is positive though because it “ticks every box that government requires”.

“It ticks the box of devolution because the local authorities and mayors want to utilise all their powers to make this a great growth story,” he says. “It ticks the box around housing, because our studies have shown that we can use the railways as an enabler to deliver up to half a million new homes.

“And then it promotes skills and provides jobs for a skilled workforce, which are hugely important.”

The “many years of work” that have gone into the development of the HS2 Phase 2b Bill is also a factor in its favour, according to Goldsby.

“There was very strong cross-party support for adapting that for LMR and that would, in effect, deliver from Millington [the mid-point between Warrington and Manchester Airport] into Piccadilly,” she says. “For the [western portion] there’s opportunity to think about the consenting process.”

As with MNWRL, the LMR hopes to attract private investment to facilitate delivery. Merriman says it is primarily looking at opportunities in the stations and utilising land value capture as has been seen in the Northern Line extension in London. In the past it has been harder to make this approach work outside of London, where land is less valuable, but the government’s pledge to rewrite the Green Book (HM Treasury’s guidance on how to appraise policies, programmes and projects for financial and social cost benefit analysis) is being welcomed and anticipated by LMR.

“That will help create a better business case,” he says. “Rail projects have previously underscored because it’s very difficult under the current scoring to take into account of all the additional benefits that a railway can deliver.”

De Cani agrees that attracting the private sector is about “demonstrating this is an attractive proposition”.

“You have to establish the right conditions in which they’ve got the freedom to do what they do best and the risk transfer is right,” he says. “How you pay them back could come from multiple sources, for example track access charges or taxation that’s generated from the growth in the Liverpool to Manchester economy.”

Phasing it all

Rather than working in competition to attract government backing, the cases for both MNWRL and LMR/NPR would be strengthened by having the other also committed.

“There’s absolutely a synergy between the two,” Goldsby says. “The two schemes are not necessarily actively being developed together because we need confirmation of how the government wants to move forward, but they complement each other in terms of broader connectivity.”

“There’s a risk that we won’t get the full benefits if they’re considered separately,” Barter adds. “We need a clear view of where we actually want rail in the North to end up, otherwise we risk ending up with something suboptimal.”

In terms of delivery, there are four distinct phases to these plans: the Staffordshire Connector, the Cheshire Connector, LMR and the rest of NPR.

It seemingly makes sense that the Staffordshire Connector be advanced first as it has planning powers in place, it would connect to HS2 and would alleviate the issue on the WCML.

By then progressing the former HS2 Phase 2b Bill to Royal Assent, the way is paved for the construction of the Cheshire Connector as a continuation of the Staffordshire Connector, taking the new line to Manchester.

Simultaneously, the Phase 2b hybrid Bill consents a chunk of LMR enabling development of that plan to kick up a notch.

The further extension of NPR across the North would be the final step, once LMR is well underway.

In this way, not only do the phases conform into a grand plan, but there is a natural stagger that benefits its delivery.

“We would have the ability to transition and phase the work across the supply chain, moving the skills from programme to programme,” Goldsby says. “It isn’t about ‘start one, finish one, start one, finish one’, it’s about taking the programme forward through its lifecycle and phasing it appropriately.

“The industry then knows what the forward pipeline looks like and can prepare to deliver, making sure we’ve got the right skills, the right technology and the right capability to see it through.”

Like what you’ve read? To receive New Civil Engineer’s daily and weekly newsletters click here.

Regional authorities are piecing together a future rail plan for growth in the North of England