Source: Regional Economies

Author: Sean O’Leary

Date published: 2025-11-11

[original article can be accessed via hyperlink at the end]

Key findings:

- Data centers like other imagined “economic game-changers” are highly capital-intensive, non-labor intensive enterprises that create few jobs and inject little money into host communities.

- While data centers are contributing more than a billion dollars annually to state and local tax revenues, they cost Pennsylvanians even more than that in higher electric bills.

- The reduction in Pennsylvanians’ spending because of higher electric bills may cause the commonwealth to lose as many jobs in the rest of the economy as data centers provide.

- With the Appalachian natural gas boom, the region has already seen investments much larger than the $110 billion scale announced by President Trump and Governor Shapiro fail to produce any measurable increase in jobs and prosperity.

Are state and local policymakers who view data centers as economic development prizes like the bull that fixates on the cape rather than the matador? And, as a result, are vast amounts of public resources being lavished on data center projects that will contribute little to jobs, tax revenues, and general economic prosperity?

Increasingly, the answer to both questions appears to be, yes.

This past week, Duquesne Light, a Pennsylvania utility that serves the Pittsburgh area, reported that the need for new electricity generating capacity, largely caused by expected data center growth, will cost existing Pennsylvania ratepayers $2.18 billion in the coming year. The figure will grow by another $538 million in 2026/2027 to about $2.75 billion, which breaks down to roughly $225 per customer per year. According to PJM, the non-profit organization that operates the electric grid in 13 Mid-Atlantic and Midwestern states and the District of Columbia, a little less than two-thirds of the increase, or $1.7 billion, is attributable to data center growth.

All of this might be OK if the data center binge were expected to deliver more than those sums in the form of additional tax revenue, jobs, and incomes for Pennsylvanians. But the funny thing is that even the data center industry itself doesn’t seem to believe that’s the case.

In April of this year, Lucas Fykes of the Data Center Coalition provided testimony to the Pennsylvania Public Utilities Commission in which he presented an economic impact study prepared by the consulting firm PwC. The study found that, in 2023 the data center industry directly contributed just $1.36 billion in state and local tax revenue. Or, put another way, data centers contributed roughly $340 million less in tax revenue than they are taking from Pennsylvania ratepayers in the form of higher electric bills. It’s a classic case of government and industry combining to give benefits with one hand while taking them away . . . and then some . . . with the other.

Now, it must be acknowledged that PwC’s tax revenue figures were for the year 2023 while the rate increase reported by Duquesne Light are for 2025 and 2026 and it is likely that tax revenues grew in the intervening year. But even if we assume a generous growth rate of 10% per year in tax revenue, the amount taken from ratepayers in the form of higher utility bills is still greater than data centers’ total contribution to tax revenue, making it a bit of a boon for government, but a kick in the teeth for people paying electric bills.

It should also be pointed out that data centers would have paid considerably more in taxes had not Pennsylvania effectively waived its sales and use tax for the industry and were county governments not inclined to offer property tax relief under Pennsylvania’s Local Economic Revitalization Tax Assistance (LERTA) program, which allows local taxing authorities to reduce property taxes by as much as 100% for up to ten years for selected projects.

“That may be true,” proponents of encouraging data center growth will say, “but aren’t data centers providing jobs and injecting money into local economies in other ways?” The answer is, yes, but it doesn’t appear to be very many jobs or very much money.

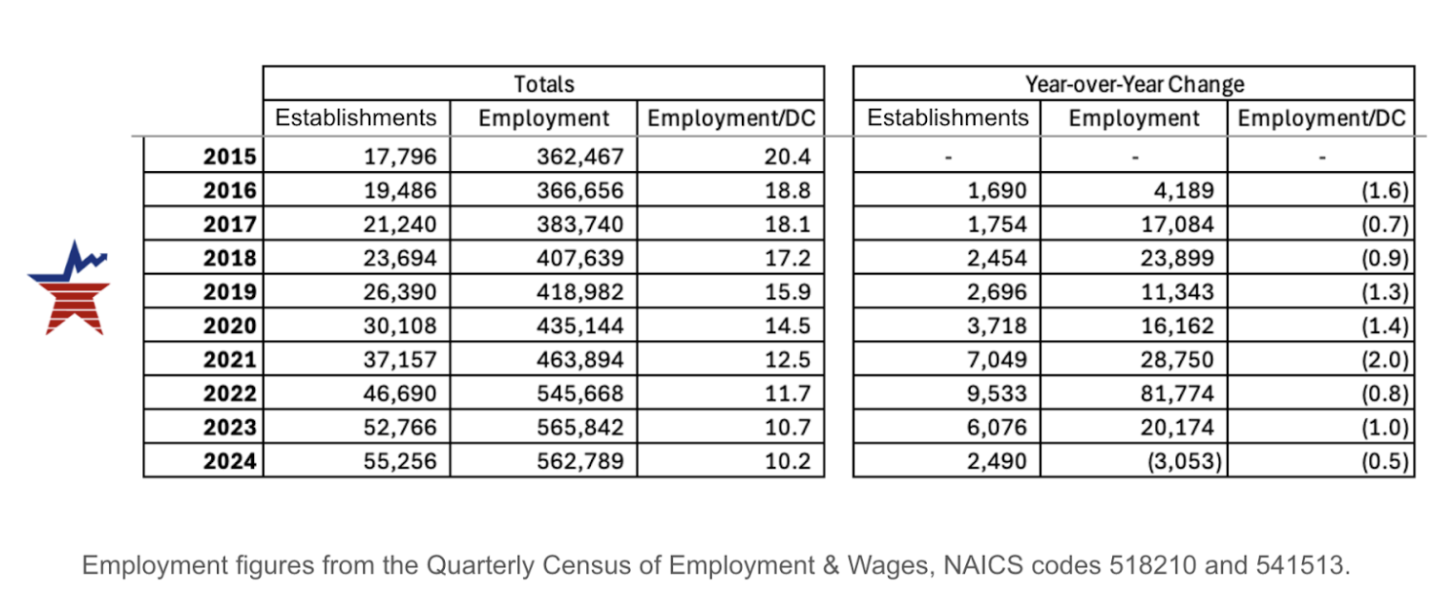

The PwC study found that in 2023 data centers directly employed 18,270 workers in Pennsylvania. At the same time, the government’s Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW) reported 15,525 data center-employed workers in Pennsylvania in 2024. We won’t quibble, either way the number is about one-quarter of one percent of jobs in the commonwealth. And we should add that, at last report, the number has not been growing. Also according to the QCEW, data center employment in Pennsylvania fell by 3% between 2022 and 2024.

In short, data center jobs are a rather negligible part of Pennsylvania’s economy. Even if they eventually triple in number as a result of the expected boom, they will still amount to less than 1% of jobs in the commonwealth. This is a reflection of the fact that data centers, like information-related businesses generally, are one of the least jobs-intensive sectors in the US economy.

In Pennsylvania, businesses that the Bureau of Economic Analysis classifies under the heading, “Information” – which includes data centers – generate about five and a half percent of gross domestic product (GDP). But they only provide 1.5% of jobs. And that low level of labor intensity is borne out when we look more narrowly, just at data centers.

In 2024, the QCEW identified 55,256 establishments nationally that are grouped in the same classification that includes data centers. That’s triple the number that existed in 2015. In 2024, these establishments employed just under 563,000 workers for an average of about 10 workers per establishment. However, these establishments include many legacy facilities that are not of the same scale as the immense data centers that are being constructed today. Still, it’s hard not to notice that the number of workers per establishment, rather than growing as data centers have gotten larger, has actually declined by half since 2015.

But, if we want to concentrate on just the new, larger data centers that are being built today, there are other ways of estimating how many people they employ. Quite a few companies develop and operate data centers. Seven of the largest – Equinix, CoreSite, CyrusOne, QTX, Center Square, Switch, and Digital Realty – operate a combined 811 data centers globally. According to employment information from the website, LeadiQ, they employ a combined 21,654 workers – an average of about 27 per data center. That’s more than the ten suggested by QCEW data, but still only about as many as are employed by an average Olive Garden restaurant.

Even if we examine industry-reported figures, which are sometimes exaggerated, the numbers aren’t much more impressive. According to C&C/WaveTech, there were 5,426 data centers in the US in 2024 and according to the PwC study, they employed 603,900 workers, an average of about 111 per data center.

Based on all of this, it’s probably safe to assume that a major data center is likely to employ somewhere between the global average of 27 workers and the industry-supported figure of 111, which means that the number of jobs it offers may range from the number of offered by an Olive Garden to the number of staff and teachers in an average American high school. While 27 to 111 jobs are welcome and good to have, numbers in this range are not economically game-changing for even the smallest counties.

It’s true that the figures I just cited do not include jobs that may arise in the rest of the economy due to data centers’ purchases of goods and services and data center employees spending their wages with local businesses. But these effects, which economic modelers call “indirect” and “induced”, should be contextualized because they are often the stuff of often wildly exaggerated claims.

In a recent Penn Capital-Star story on data center expectations in western Pennsylvania, Eric Jankiewicz reported that, “The Allegheny Conference on Community Development counts eight coming data center projects and related gas and nuclear energy developments that “could support nearly 200,000 jobs throughout Southwestern Pennsylvania on a direct, indirect, and induced basis” and have an estimated economic impact of $20 billion.”

If this were accurate, it would come to 25,000 jobs per data center or roughly 250 indirect and induced jobs for every job directly created by a data center. IMPLAN, the company that provides the most popular economic impact modeling software, suggests that most of the time, job multipliers at the state level fall between two and three, not the 250 imagined by the Allegheny Conference. That said, IMPLAN acknowledges that multipliers can “vary greatly,” although it’s doubtful that anyone would be so bold as to claim that they number in the hundreds.

There are also likely to be other problems with the Allegheny Conference study, which that organization has chosen not to share with ORVI or the reporter, Eric Jankiewicz. For instance, the authors almost certainly did not consider the detrimental impacts of $2.75 billion being added to Pennsylvanians’ electric bills. If we treat this figure as lost income for Pennsylvania households, IMPLAN’s modeling software tells us that, due to resulting declines in purchasing, it would cause the loss in Pennsylvania of 17,268 jobs and over $200 million in state and local tax revenue.

These effects were almost certainly not considered in the PwC/Data Center Coalition and Allegheny Conference economic impact studies. Rarely do industry-sponsored studies examine costs that are associated with the projects they’re written to promote.

However, to be fair, the quote from the Allegheny Conference suggested that data centers’ economic impact should be considered in combination with that of related projects, such as natural gas and nuclear power plants that will be required to power data centers. They might also want to include the extraction of the natural gas that will be used to fuel the plants that power data centers. So, let’s go down that path.

The construction of new nuclear-powered data centers is something that is years if not decades away. But natural gas plants can be built now and are the most likely power sources for most data centers in Pennsylvania in the foreseeable future. And their economic impacts are well known.

Many gas-fired power plants fall into the range of between 1,000 and 2,000 megawatts of capacity, which is enough to power a large data center or a small city. The average 1,000 to 2,000 megawatt natural gas-fired power plant employs about 30 people. In other words, gas plants, like data centers, fall into that category of enterprises that are highly capital-intensive and not labor-intensive and they fall squarely in the Olive Garden class of job providers – nice but not of immense economic impact.

We can see the evidence throughout the region.1,000 to 2,000 MW gas plants in Westmoreland County, PA, Lawrence County, PA, and Guernsey County, Ohio all fall into this category, employing between 20 and 30 people each. And, even if we drive the analysis further upstream to take into account the employment and economic impacts of producing the gas required to fuel the power plants, we will continue to be disappointed. Because natural gas production and processing is, like data centers and power plants, another highly capital-intensive and not very labor-intensive enterprise. In fact, in that regard, it’s the worst of the lot.

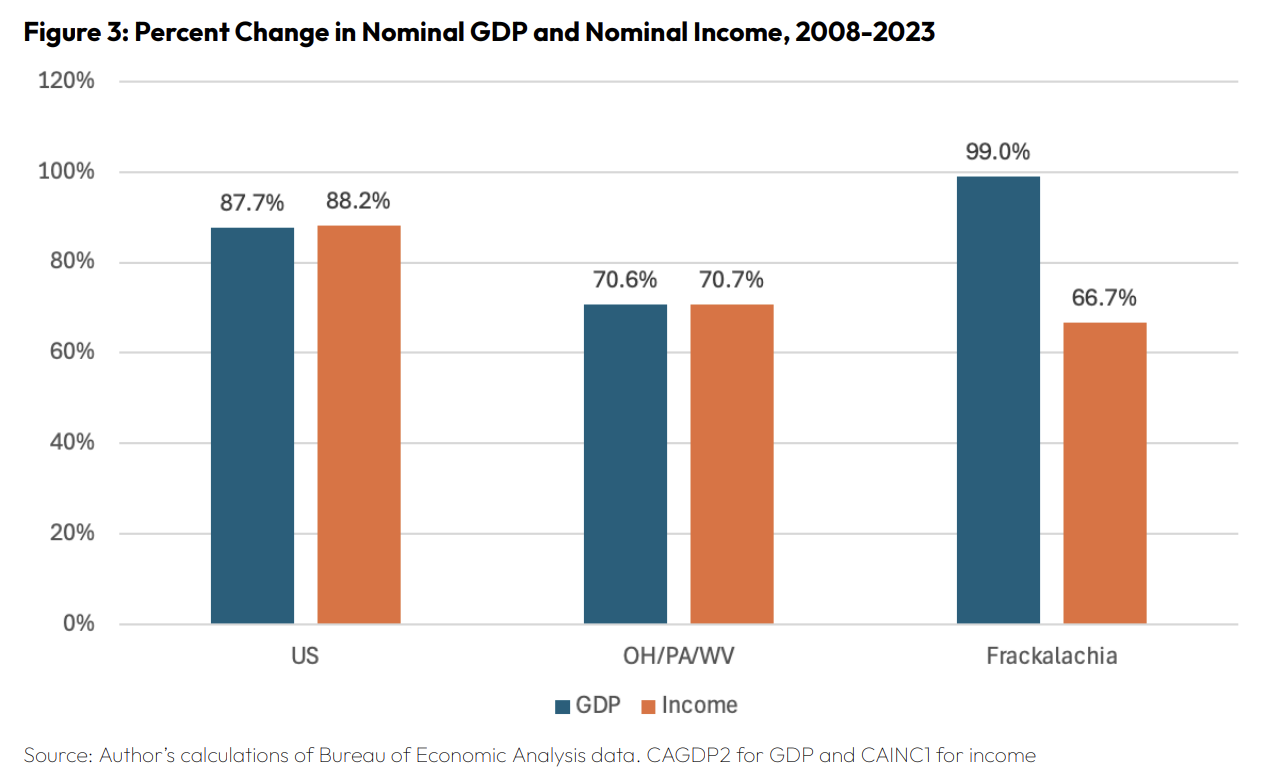

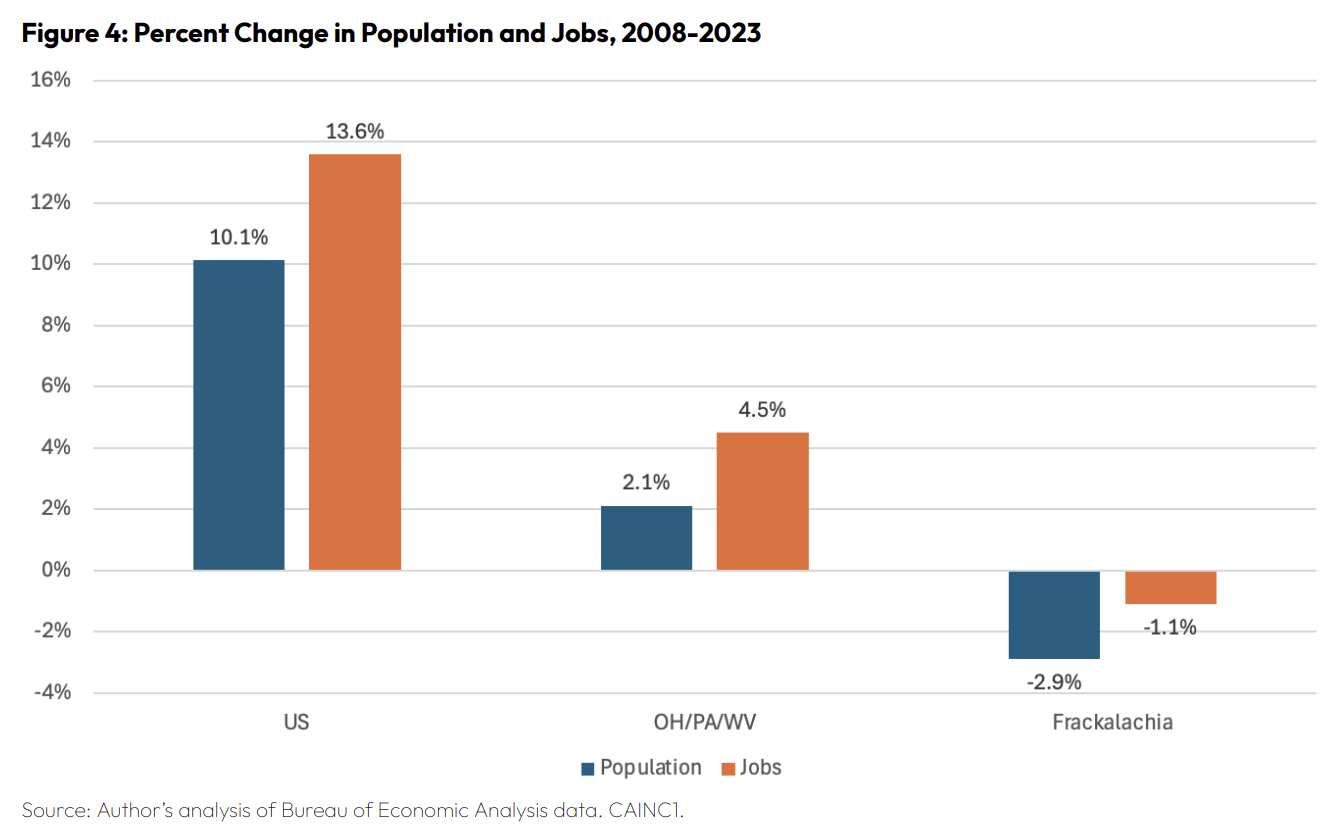

That is why, as the Ohio River Valley Institute has documented in a series of reports starting in 2021, the thirty major gas-producing counties in Appalachian Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia, far from experiencing growth in jobs and income, have experienced ongoing job and population losses since the beginning of the region’s fracking boom. That is despite the far better-than-average GDP growth brought about by the boom and, as we shall see in a moment, immense amounts of money invested by the industry.

That is why, as the Ohio River Valley Institute has documented in a series of reports starting in 2021, the thirty major gas-producing counties in Appalachian Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia, far from experiencing growth in jobs and income, have experienced ongoing job and population losses since the beginning of the region’s fracking boom. That is despite the far better-than-average GDP growth brought about by the boom and, as we shall see in a moment, immense amounts of money invested by the industry.

The following charts illustrate the economic paradox of “Frackalachia” – Appalachia’s gas-producing counties – where GDP growth outstrips that of the nation, meanwhile measures of local prosperity plummet. We see that, despite Frackalachia outperforming the nation and states in the region for GDP growth, it lags the nation and the combined states of Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia for income growth.

And the effect on jobs and population is even more depressing.

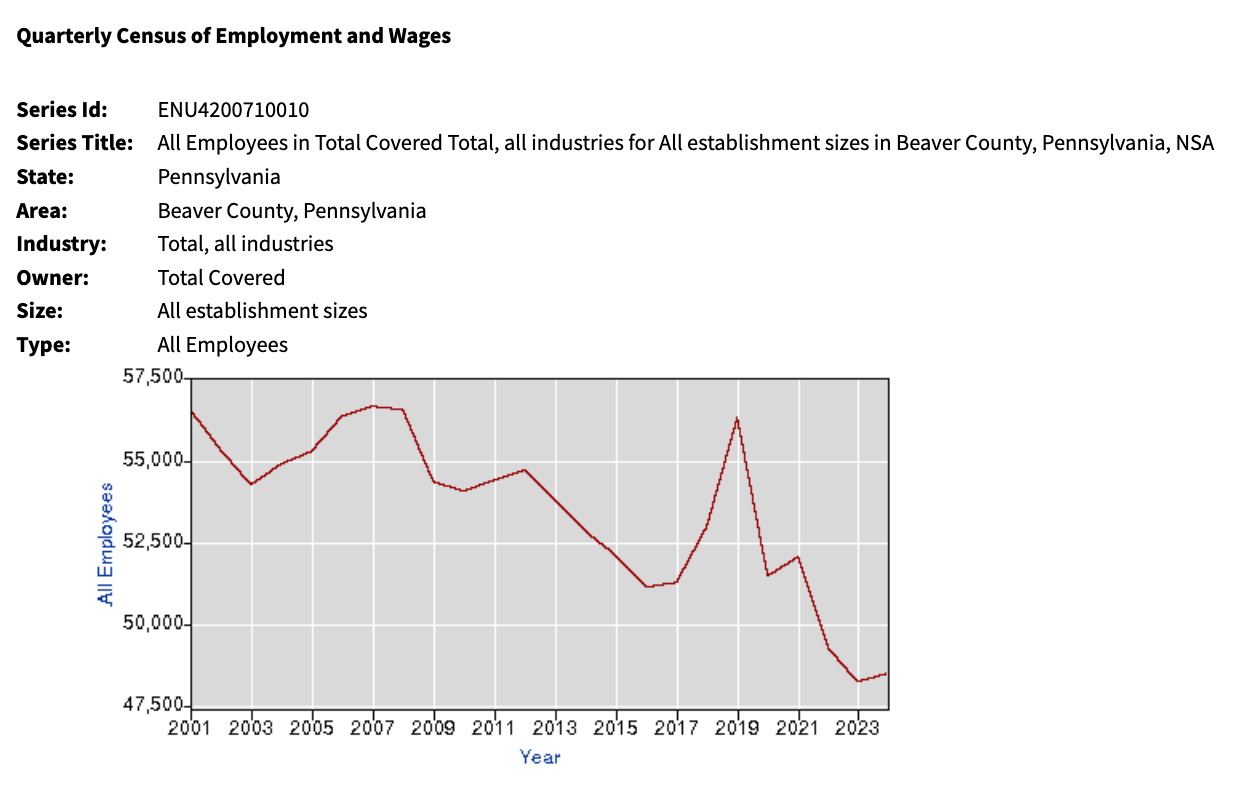

There is, however, at least one positive economic outcome that data centers are likely to produce. It occurs when they’re being built. Their construction provides lots of jobs in the building trades and in companies that supply the building trades. For a year or two, communities that host data centers will see large spikes in employment and income as well as increased commerce in hotels, motels, and restaurants. We saw it happen a few years ago in Beaver County, Pennsylvania when the Shell Petrochemical Complex, often referred to as the Shell cracker, went under construction. However, the problem from an economic development standpoint is that construction jobs are temporary. As we see in a QCEW chart for Beaver County, once construction, which began in 2017, was largely completed in 2020, economic trends reverted to what they had been before the project began. And, because the Shell cracker is yet another example of a highly capital-intensive and non-labor-intensive enterprise, the beginning of operations at the newly-completed plant had little impact on the local economy. And that facility employs 400 people, probably far more than most data centers.

This should all be bracing for people and policymakers in particular who put their faith in industry-sponsored economic impact studies. At the beginning of the Appalachian natural gas boom, the American Petroleum Institute published economic impact studies that predicted 200,000 new jobs in Pennsylvania. Fifteen years later and notwithstanding the fact natural gas production has indeed skyrocketed, surpassing even API’s expectations, there is no evidence that the gas boom has produced much if any job growth in Pennsylvania.

Similarly, the Shell cracker was the first component of what an American Chemistry Council economic impact study said could be the beginning of a second American petrochemical cluster – the first being found along the Gulf Coast. The study predicted the creation of 100,000 jobs. And Shell itself commissioned two similarly designed economic impact studies from Robert Morris University, which also predicted immense contributions to jobs, wages, and tax revenues. However, today, apart from the 400 employed at the Shell facility, no other projects or jobs that were envisioned as part of the imagined petrochemical cluster have ever materialized.

Meanwhile, local and state policymakers squandered immense amounts of public money and resources in support of the cracker in the expectation that jobs and economic prosperity would follow. They did not. And now, because data centers share with fracking, with power generation and with petrochemicals the fatal characteristic of being highly capital intensive and non-labor-intensive, they will likely produce similar economic outcomes.

This outlook is admittedly bleak, but there is still one more important point to be made. Despite the facts cited above, some readers, which may include state and local policymakers, will consider the arguments presented and then turn and look at newspaper headlines from just a couple of months ago, when $92 billion in technology investments in Pennsylvania – later increased to $110 billion – were announced by President Trump at Carnegie Mellon University.

And, when they recall that occasion, they’ll look again at the facts recounted here and think to themselves, “Yes, but we’re going to receive $110 billion in investments. How can an amount that great not induce jobs and prosperity or at least have a major beneficial impact? Maybe it won’t be as great as the Allegheny Conference imagines, but still . . .”

The answer, sadly, is that not only can investments on that scale have little or no beneficial impact, we have already seen it happen in our region.

Just a moment ago, I recounted the story of Frackalachia and its thirty gas-producing counties that saw investment and economic output skyrocket while the counties experienced absolute losses of jobs and population. Eight of those thirty counties are in eastern Ohio. And, thanks to the efforts of folks at Cleveland State University, we know how much money has been invested to build Ohio’s natural gas industry. The figure, which represents the combined expenditures by the industry since roughly 2008 at the dawn of the fracking boom, recently reached $110 billion.

“What a coincidence!”, you might say. “$110 billion again!”. And, indeed, it is a remarkable coincidence that the same amount of investment should pop up again. But, more than a coincidence, it should also be seen as a warning from the gods about the risks of irrational exuberance and the threat that once again the region’s policymakers will blunder their way down what has already proven to be a doomed path.

The eight Frackalachian counties in Ohio, which were the principal recipients of the $110 billion in investments – more than $30,000 for every man, woman, and child that lives there – have, even among the suffering Frackalachian counties, suffered more than the others.

Since the beginning of the natural gas boom:

- The number of jobs in the 8 counties plunged by 10,863 or almost 11%.

- The counties’ combined population declined by nearly 28,000 people or 8%.

- The combined incomes of people who live in the eight counties grew by only two-thirds the amount of income growth nationally.

So, when so much has been invested, how can this happen? Where does all that money that’s ostensibly being invested go? A hint is provided by a recently released analysis, from Bank of America, of the cost to build a data center.

Only about 2.5% of the dollars invested to stand up a data center goes to construction, which might employ local workers. 75% goes for servers and networking hardware in which there is minimal if any local participation. The rest is mostly for power-related equipment, nearly all of which is likely to be built elsewhere and merely installed locally.

This phenomenon mirrors that which happened with the natural gas boom in the region and with the Shell cracker. While immense sums are “invested”, little of that investment is actually made locally. Moreover, as with the natural gas boom, once new data centers go into operation, little of the revenue they earn will enter local economies either through wages or taxes since Pennsylvania leaders chose to waive sales and use taxes, a measure surrounding states have also taken.

Data centers’ characteristic capital-intensity and non-labor-intensity, combined with the commonwealth’s and localities’ sacrifice of tax revenues, constitutes a structural barrier to data centers becoming the economic development engines Pennsylvanians and their leaders hope for. And the only way to change the inevitable disappointing outcome is for policymakers to recognize data centers for what they are and tax and regulate them fairly to insure that a significant portion of the investment they command and the sales revenue they generate stays in Pennsylvania and lands in local economies. And, if by doing so we risk losing data center development to other states, the appropriate reaction should be, “So what? If they don’t pay their fair share in taxes and if they don’t pay for the added electricity and infrastructure that they necessitate, then they’re not going to contribute meaningfully to jobs and prosperity anyway.”

The post Why Data Centers Will Be Economic Development Duds appeared first on Ohio River Valley Institute.

View original article at:

https://ohiorivervalleyinstitute.org/why-data-centers-will-be-economic-development-duds/