Source: Local Growth and the United Kingdom

Author: Adam Yousef, Senior Manager

Date published: 2025-08-28

[original article can be accessed via hyperlink at the end]

While it is widely acknowledged that the UK’s poor investment record is undermining both productivity and sustainable growth, it is important that any investment is targeted at specific sectors and activities as opposed to being broadly scattered. In a rapidly-evolving economic context that includes the emergence of ‘new economy’ sectors and decarbonisation, such a judicious approach to investment promotion is more important than ever.

This supplement presents a broader discussion of potential approaches that could be adopted to address areas of underinvestment in London and the UK, and by extension tackling the productivity puzzle and relatively feeble growth that both have experienced since the 2008 Financial Crisis.

Before delving into the details, it is worth reminding ourselves of the definitions used by the ONS[1] to define certain important terms:

- Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF): an estimate of net capital expenditure by both the public and private sectors.

- Business investment: Net capital expenditure by businesses within the UK; they exclude expenditure on dwellings and the costs associated with the transfer of ownership of non-produced assets, and capital expenditure by local and central government.

- Chained volume, seasonally-adjusted data: This supplement will only look at chained volume, seasonally-adjusted GFCF data as it would adjust for the impact of inflation over time as well as reveal underlying movements rather than incorporate seasonal variation in investment. For example, retailers typically hold more inventories in the run-up to Christmas and government organisations tend to spend more in Quarter 1 of each year at the end of the financial year. The seasonally-adjusted data removes such effects.

1. Reversing business underinvestment and poor capital formation

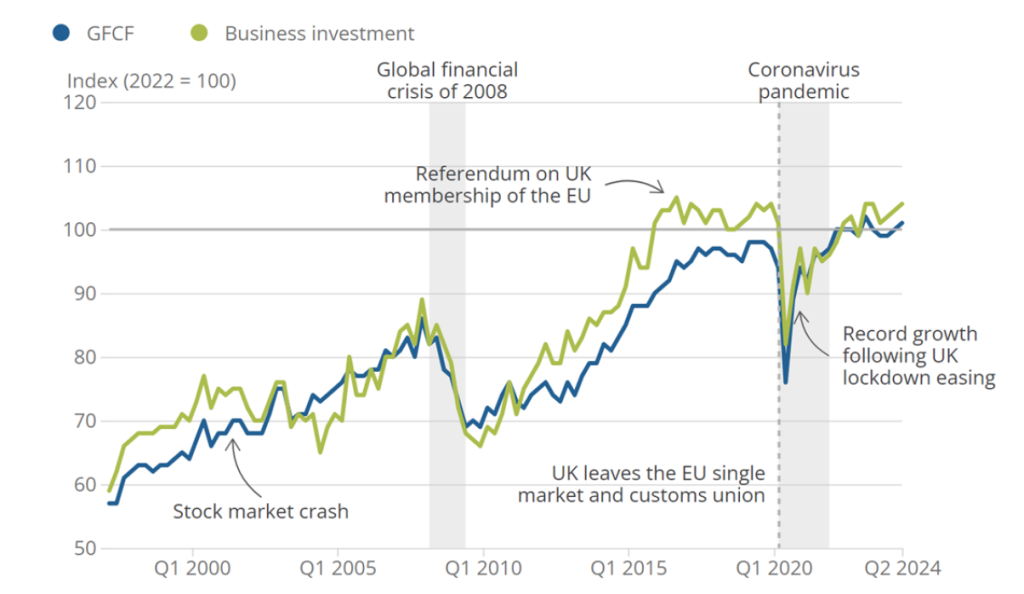

It is important to note that the latest ONS data on business investment show that it had only returned to pre-pandemic levels in the 2nd quarter of 2024 (see Figure A1). Not only that, but levels are virtually identical to where they were at the time of the 2016 Brexit referendum. By comparison, the picture is slightly better for GFCF; levels are nearly back to where they were in 2022 and slightly higher than where they were pre-COVID. That said, business investment has been increasing faster than GFCF since 2022.

Figure A1: Business investment and GFCF in the UK (1997-2024)

Source: Office for National Statistics

Meanwhile, compared to other OECD countries, the UK’s performance on private-sector business investment remains underwhelming – in 2022, it ranked 28th out of 31 OECD countries and the lowest within the G7 since 2020. Moreover, the UK scored at the bottom of the G7 in business investment in 24 of the past 30 years.

With private businesses responsible for the lion’s share of job creation in the London and UK economies, no comprehensive solution to the investment, productivity and growth challenges could bypass this issue. The discussion on private-sector investment promotion typically centres on the competitiveness of corporate tax rates. That said, recent economic evidence paints a more complex picture where business investment decisions overly rely on other factors, including but not limited to the provision of civil and transport infrastructure to facilitate production across different phases of the supply chain, political stability, a credible and robust national economic strategy, and subsidies and tax incentives to reduce business expenses (especially those related to innovation and R&D). Moreover, various studies have pointed to poorer management practices in the UK as a reason, singling out management’s limited focus on investment and growth (compared to the US and other G7 countries) and the limited pressure from their seniors to do so (which correlates with the increasingly remote nature of ownership of UK-based enterprises).

Another major challenge to boosting business investment in the UK is that UK-based pension funds do not invest sufficiently in local businesses and alternative assets. For example, defined contribution (DC) schemes tend to be relatively small and fragmented, which inhibits them from making meaningful investment in UK business. To address this challenge would require measures to boost pension plan consolidation. Moreover, certain studies recommended that central government devolve ‘strategic planning powers’ on pension-fund investments to regional and combined authorities to ensure that such investments are channelled into sectors that would enhance outcomes in alignment with local growth plans.

Last but not least, providing a greater voice for workers in the management and administration of UK businesses could promote further investment and boost productivity, as evidence from South Korea and Europe suggests, while further support to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which employ over 40% of Londoners and just under 40% of people in the UK, could certainly help such businesses navigate problems with access to finance and long-term capital.

Many of these potential solutions could also address the problems associated with GFCF accumulation. That said, as GFCF also includes public sector investment, a possible challenge would be public-sector underinvestment to alleviate budgetary pressures (see next section).

2. Ensuring adequate levels of public-sector investment

The share of GDP dedicated to capital formation has been low in the UK compared to the US, France and Germany in most years since the 1960s, and the gap has widened further since the late 2000s. Data from UNESCO shows that on average, between 2016 and 2022, UK government investment in R&D as a percent of GDP lagged that of many peers, including the US, Germany, Japan, South Korea, and Switzerland. In addition, in 2020, the UK devoted only 1.7% of its GDP on R&D expenditure, compared to France (2.3%), Germany (3.1%), and the US (3.5%). Increasing government spending on R&D as a percent of GDP is imperative in light of the gap between the UK and peer countries who also happen to outperform the country on productivity growth.

That said, public investment should also be targeted at civil and transport infrastructure. OECD data for 2021 shows that the UK’s investment in infrastructure (rail, road, and air) lags that of France, Germany, Japan, and the United States. The economic literature clearly demonstrates the positive impact that infrastructure investment has on economic growth- whether by reducing production costs, increasing the productivity of capital, labour and other inputs, or by generating positive externalities that benefit the wider society. Research from the United States shows that the ‘multiplier’ effects of infrastructure investment are greater than those of other types of fiscal intervention, so that “each $100 billion in infrastructure spending would boost job growth by roughly 1 million full-time equivalents (FTEs)”. That said, evidence from the UK would suggest that any such benefits would only materialise in the long run, as in the shorter term transport infrastructure does not significantly promote economic growth and development.

3. Promoting London’s role as an incubator of innovation clusters

There is little doubt that nationally, London is the predominant engine driving national economic growth while also holding a competitive advantage in the very sectors that the country needs to retain its global economic competitiveness in the future. Most of these sectors are knowledge-based and rely on innovation to generate the products and services they produce and export. Capitalising on the city’s strong reach in these areas is a positive-sum game for the rest of the country, and supporting growth of the city’s innovation clusters (across different regions and sectors) is critical.

Recent analysis by Greater London Authority economists using innovative Real-Time Industrial Classification (RTIC) data provided by consultants The Data City points to the following sectors as key incubators of innovation and primary components of future growth:

- Fintech: This would include alternative credit, consensus services, crypto-asset exchange, digital banks, digital capital raising, digital custody, digital identity and lending, digital payments and savings, tech-based insurance, and tech-based wealth management. More than 55% of London-registered Fintech businesses are based in Inner London boroughs that are part of the Central Activities Zone (CAZ), which gives this region significant clout in ensuring sustainable economic growth nationally.

- Artificial Intelligence (AI): This includes blockchain, advanced data analysis, enabling platforms, green technology, image processing, automation, and machine learning as examples. AI companies exist and are registered in all of London’s boroughs, with most concentrating in the CAZ.

- Creative Industries: This sector includes digital creative industries (e.g., advertising, architecture, culture and heritage, and design), photography, streaming, gaming, media and publishing. Across London, 3,370 creative industry companies are registered, with those tending to cluster in so-called Creative Enterprise Zones (CEZs) that spatially encompass artists and small creative businesses.

- Life Sciences: This sector includes biotech, life sciences manufacturing, “Pharma”, “Medtech” and biopharmaceuticals. London includes just under 2,000 such companies across all boroughs, and these also tend to cluster in Inner London boroughs (where known life sciences clusters such as MedCity are established).

- Net Zero: This sector covers energy generation, energy management, energy storage, clean technology and low emissions products and services. With over 4,400 companies, London shines in this sector, with clusters found beyond the CAZ area.

These sectors are likely to remain critical if London and the UK are to transition ecologically and economically towards a more sustainable path to protecting living standards. With London already enjoying a competitive edge in attracting businesses to such sectors and effectively reaping the agglomeration rewards underpinning such clustering, the city is in a privileged position to support the UK’s drive towards higher and more sustainable economic growth.

In summary, we can deduce the following:

- The UK continues to lag peer countries in fostering business investment and accumulating gross fixed capital formation. This has played a significant role in undermining productivity and growth.

- Promoting business investment should go beyond reducing the headline corporation tax rate to examine the other subsidies and tax incentives that could be provided to support businesses with their investment needs (in particular SMEs), investment in infrastructure to reduce business costs, encourage regulatory reforms that would incentivise pension schemes to consolidate and invest domestically, and strategies to promote better management practices and greater employee participation in setting businesses’ strategic direction.

- Given London’s predominant economic position nationally and its competitive advantage in sectors of the ‘knowledge-based economy’, a national/regional combined strategy that supports London’s existing and emerging innovation clusters in key sectors of the new economy would undoubtedly support national efforts to boost economic growth while accounting for the multifarious economic shocks and needs posed by the ongoing environmental transition.

Finally, it should be emphasised that addressing underinvestment is one piece of a bigger and more complex puzzle that relates to London’s and the UK’s poor productivity and growth record since 2008.

[1] Taken from the following source: ONS (2017). ‘A short guide to gross fixed capital formation and business investment’, May 2017.