Source: Local Economies (UK)

Author: Angelica Ottaway

Date published: 2026-02-12

[original article can be accessed via hyperlink at the end]

Britain is not a country at ease. Over the past 18 months, in conversations we’ve had with over a hundred squeezed workers, carers and others in places from Warrington to Worcester, there has been persistent sense that life has become harder. For many, the deterioration feels recent and rapid. But the data suggests something more troubling: today’s malaise is the product of a slow-burning squeeze that has been building for two decades.

Our new book, out today, set this out, exposing and analysing the experience of what we call “Unsung Britain” – the 13 million working-age families (containing 27 million people) living in the bottom half of the disposable income distribution, and showing what a policy agenda focused on this group would entail.

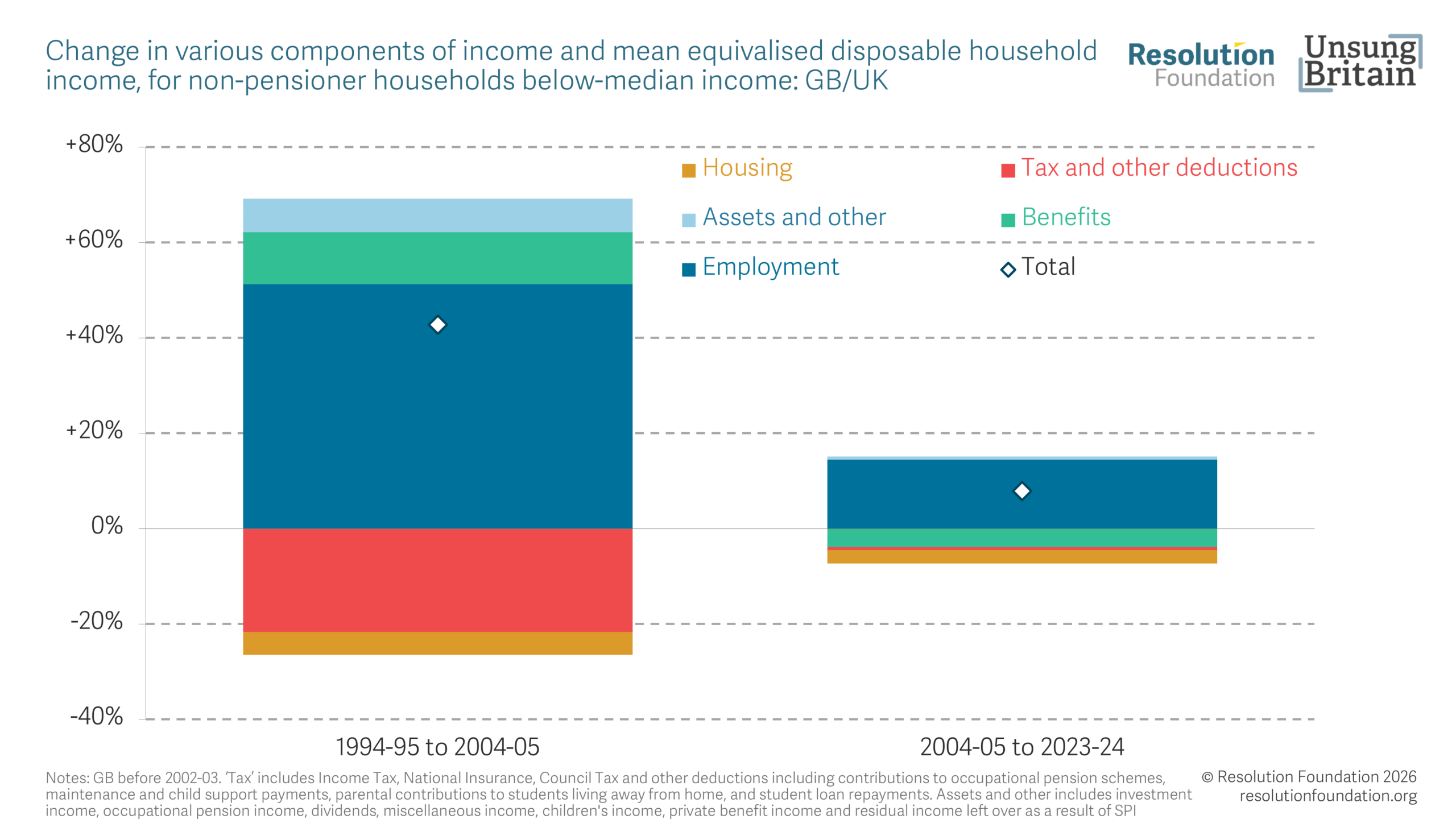

These families are working more, caring more, and contributing more than in previous generations, yet the rewards for those efforts have stagnated. Typical disposable incomes for this group have grown by just 0.5 per cent a year since the mid-2000s – a fraction of the growth enjoyed in previous decades. In the 40 years leading up to 2004-05, incomes for similar families doubled. At today’s pace, achieving the same improvement would take over 130 years. This stagnation affects higher-income families too, but it is especially worrying that incomes among households near the bottom have fallen outright over the past two decades.

More work, limited reward

These disappointing outcomes arise despite Unsung Britain working more. The employment rate among the bottom half is up by 11 per cent since the mid-1990s, accounting for the entire increase in the UK employment rate since the mid-1990s. The minimum wage has also delivered substantial real gains, helping to narrow pay inequality.

But the UK’s widespread slowdown in earnings growth since the mid-2000s mean that this stronger employment and fairer wages have not turned into improvements in living standards for Unsung Britain. If we look at the real-terms growth in earnings of people in below-middle-income families since the mid-1990s, three-quarters of that increase took place before 2005.

Without solving the UK’s productivity slowdown, Unsung Britain will never see sustained increases in earnings, and the Government must not row back on its quest to get growth up. But low-wage work can also be insecure, unrewarding and unregulated, and so the Government should push on with the ‘Fair Pay Agreement’ model for social care – a potential model for other sectors too – and ensure that the new rights that employees are set to gain come with effective enforcement.

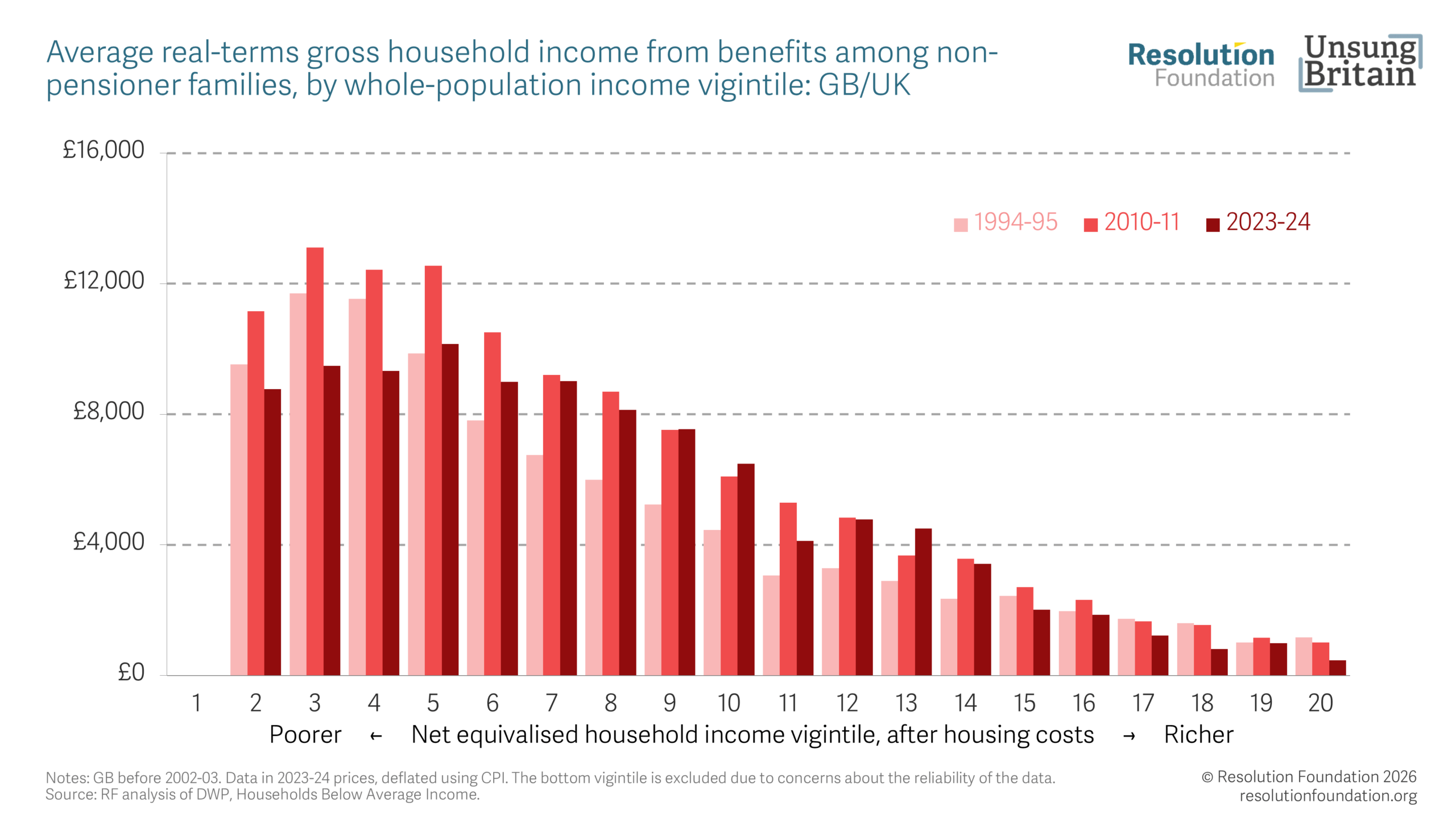

A weaker safety net

Stagnant pay is only part of the story. Changes to the welfare system boosted incomes in the 2000s, but working-age benefits have been squeezed repeatedly since 2010 through freezes and targeted cuts – although these cuts took place alongside rising spending on pensions and disability benefits, meaning overall welfare spending has not fallen. A social security system designed for lower-income families must address the drivers for higher demand for health-related benefits, but also introduce consistent indexation of benefits, with all working-age benefits and the state pension rising with earnings, and Local Housing Allowance for private renters re-linked to actual rents.

The rising cost of essentials

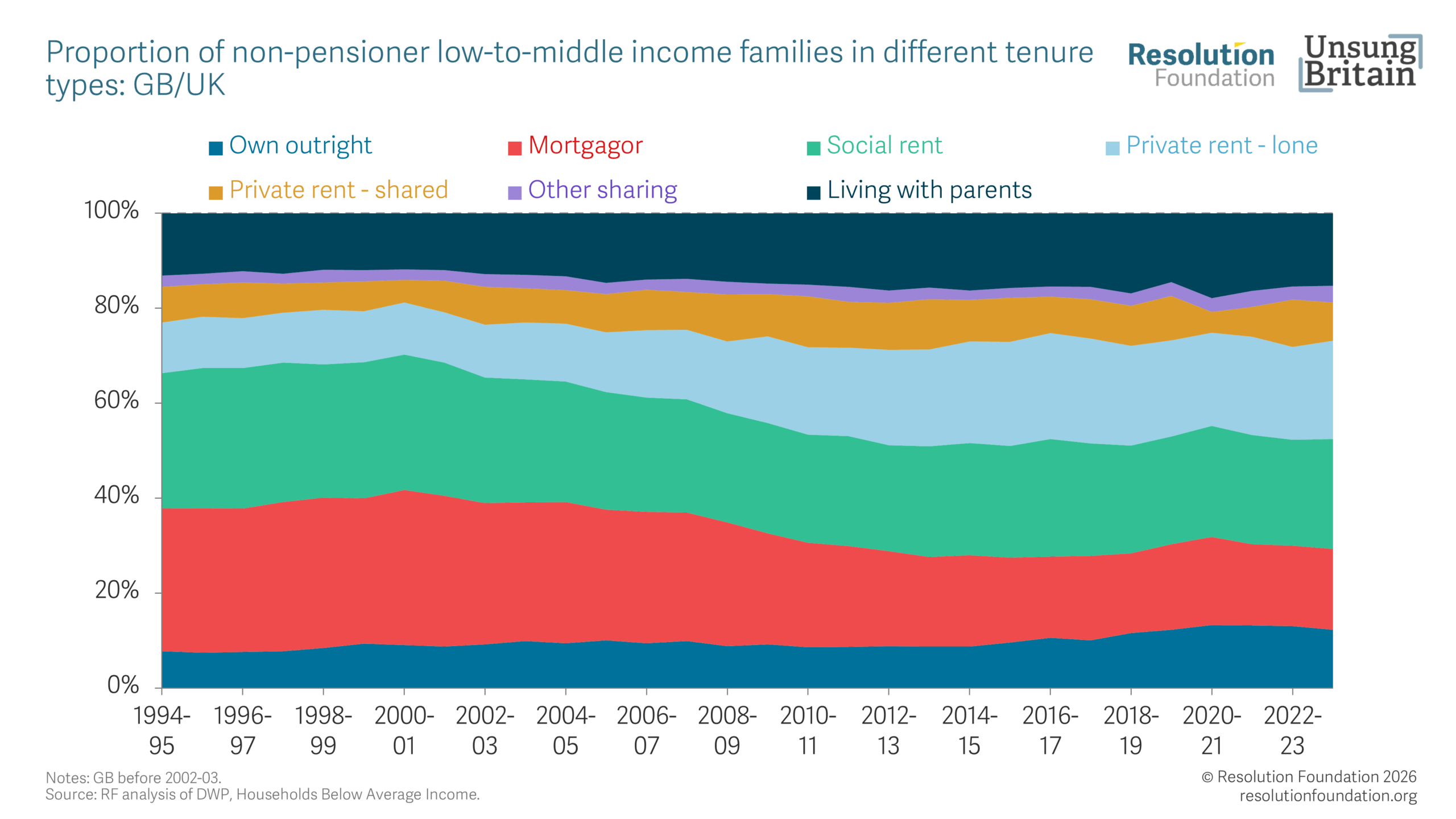

For Unsung Britain, what goes out each month matters just as much as what comes in. Housing is one of the most powerful drivers of financial strain. The last generation has seen a sharp shift away from home ownership and towards private renting, with around 8.6 million lower-income Britons now living in the private rented sector, where housing costs consume, on average, 43 per cent of disposable income. High rents have other implications: remarkably, there are almost as many families across lower-income Britain at home with their parents as there are buying their home with a mortgage.

Other unavoidable costs have also become more burdensome. Council Tax has grown increasingly regressive, while recent inflation – particularly in energy and food – has hit lower-income households hardest. The result has been a surge in arrears on both energy bills and local taxes, with financial strain is shifting from consumer credit into essential household bills.

Reducing these pressures will require structural reform, including expanding housebuilding (particularly social housing), rethinking property taxation, a real ‘social tariff’ in energy, and a relentless focus on ensuring all markets work for consumers.

Health, care and economic participation

The challenges facing Unsung Britain extend beyond pay and prices. Health inequalities have widened, with large gaps in healthy life expectancy between richer and poorer communities. Disability is also rising, particularly among working-age adults, with mental health problems playing a growing role. Almost a third of poorer disabled people report being unable to work because of their health.

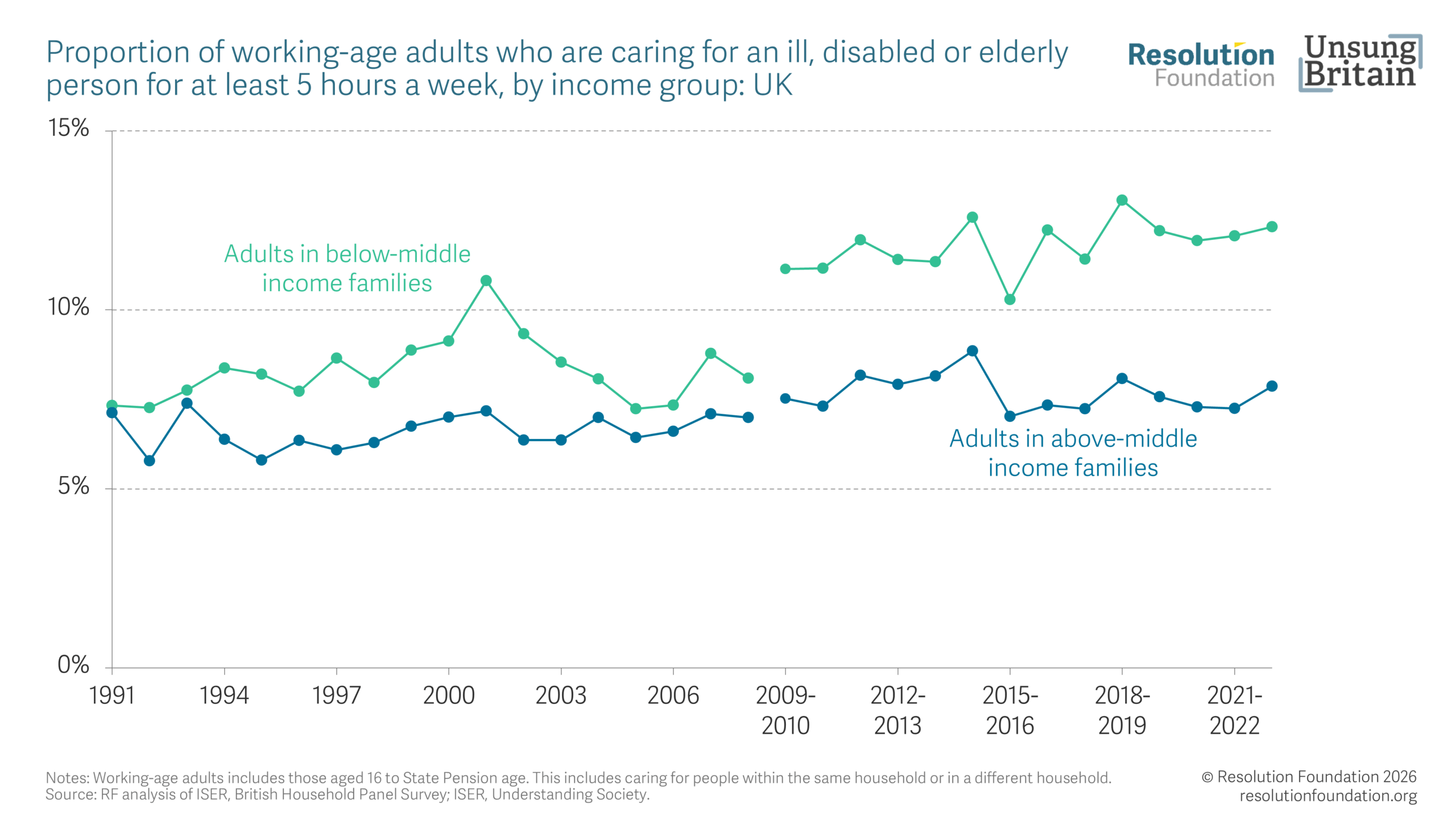

Alongside this sits a widening care gap between lower- and higher-income families, a burden that falls disproportionately on older women. In homes of modest means, one million people have care responsibilities of 35-plus hours a week, obligations on a scale that is likely to make full-time paid work impossible. The rising incidence of ill-health and obligations to care for people who are sick, elderly or disabled was the most surprising new fact, to me: over four-in-ten families in Unsung Britain contain either a carer, or someone with a disability. Without stronger support for disabled people and carers – including better workplace protections, expanded carers’ leave, and investment in our mental health – progress on living standards will remain constrained.

A test for policymakers

The story of Unsung Britain is not one of economic collapse, but of prolonged stagnation over two decades, combined with rising pressures from housing, health, caring responsibilities and essential costs.

Reversing that trajectory will require a strategy that links stronger economic growth with targeted reforms to wages, housing, social security and public services. We call the families at the sharp end of Britain’s squeeze “unsung” because they have contributed more to the country’s prosperity than is often recognised. The challenge for policymakers now is to ensure they share more fully in it.

The book we’ve published today, and launched at a conference, comes at a time of high political drama. But we should also step back from this week’s fast-moving events to consider the longer-term picture of economic malaise. Until that is turned around, and strong, sustained rises in living standards are secured, it’s hard to see how the doom loop of distrust and disillusionment with politicians and political institutions will end.

The post Unsung Britain: working harder, getting nowhere appeared first on Resolution Foundation.